JOURNEY of CONSCIENCE

Visiting the WWII Japanese American Internment Camps

From Manzanar to Minidoka…

Dear friends… It looks like my journey has drawn to an end. Not that I will ever cease looking into and thinking about this tragic chapter of American life. Not that I will ever forget the courageous responses of so many Americans who were treated so unjustly. It’s just that arthritis in lower back vertebrae (from working in heavy construction as a teenager) has created too much pain for any more long, driving trips.

So, I thought I would offer a reprise of sorts, sharing some of my favorite posts, starting with Manzanar and ending with Minidoka… Here we go.

IT WAS A PRISON CAMP…

Manzanar and the nine other WRA Camps were called all manner of things. FDR first referred to them as “Concentration camps,” when his administration was considering the detainment of over 110,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry. As they rolled out the detainment, the administration shifted to the term “Relocation camps,” almost as though they were undertaking some benign, even helpful enterprise. Reinforcing this perspective, some called them “Evacuation camps” in a process of “Evacuation,” suggesting that the WRA Camps were even designed to protect these Japanese Americans from hostility and violence on the part of their fellow Americans. “Internment camps” became a phrase that stuck in official and unofficial parlance.

As you get close to Manzanar, the most notable landmark is the reconstructed guard tower. There were eight towers that surrounded the residential compound at Manzanar. They were manned 24 hours a day by armed guards. The towers included searchlights that scanned the camp in the hours of darkness. The purpose was clearly to maintain control of the people living inside the camp and to prevent escape. Manzanar was a prison camp that held Americans without due process, Americans who were neither charged with nor convicted of any crime.

“The sight of the barbed wire enclosure with armed soldiers standing guard as our bus turned slowly through the gate stunned us… Here was a camp of sheds enclosed with a high barbed wire fence, with guard towers and soldiers with machine guns.”

Estelle Ishigo, Manzanar, from “Infamy,” by Richard Reeves

“When I asked my mother, ‘Why are we here, why are we in this prison?’… She said simply, ‘It’s because we’re Japanese.’ ”

Unknown child in Manzanar, from NPS video, “Remembering Manzanar”

Manzanar was a prison camp. It was a city, the largest in the Owens Valley, and one with several amenities. There was healthcare, there were places of worship, there were schools, and there was plenty of food. There was generally freedom to move throughout the camp. But the people were held captive against their will. They lived in barracks, ate in mess halls, and went to the bathroom and showered in latrines with no partitions. There was no privacy in any of the buildings available to them. It was the intimacy of forced communal living.

In the days to come, you will see pictures and read commentary about the various aspects of life at Manzanar. The National Park Service has done a careful job of providing a historically based recreation of Manzanar. I will do my best to show it to you with my photos. In addition, the Densho Encyclopedia, the NPS, and other sources have recorded and archived a host of interviews with people who lived in the camps. In my coming posts, I will share quotes from some of those sources.

As I continue this part of my journey, walking through Manzanar, come along with me. I hope my photos and reflections, and especially the commentary of people who lived there, will bring Manzanar to life for you.

NOTE: If you are having trouble seeing all of the posts, click the Journey of Conscience banner at the top of the page.

THANKS for joining me! If you’d like to follow this blog, just scroll all the way to the bottom of the page and click the “Follow” button. If you feel so moved, share this blog with others as well.

LIVING IN BARRACKS…

Have you ever lived in military barracks? The worst military barracks of our era (constructed shortly after World War II and used at least through the Vietnam War) were far better than the barracks at Manzanar. For one thing, the military barracks were solidly built, and held out the wind, rain, fog, and dust. They generally had linoleum or tile over a wood or concrete base. It was possible (and required) to mop and wax them regularly to keep them shining. Dust particles were not allowed to accumulate. There was ample light and heat. Finally, there were only soldiers, sailors, or marines in those military barracks.

Here are some facts about people who lived in barracks at Manzanar.

- There were 10,046 people in Manzanar.

- There were 504 barracks, each with 4 “apartments.”

- Authorities planned for 8 people per “apartment.”

- Unrelated single persons lived in barracks apart from families.

The people who were taken to Manzanar were in for a shock about the sorry state of their living quarters. For starters, only some of the barracks were completed when people began arriving. The rest had to be built in haste. In the hurried process, green lumber was used. That green lumber was sure to dry up quickly in the harsh Owens Valley climate, and thereby create gaps in the roofs, the walls, and the flooring.

The problem with the green lumber wouldn’t have been as bad, if the barracks had been designed and built properly. However, the exterior, wood frame walls consisted of pine boards covered with tarpaper (with thin wood slats to hold that in place). There was no proper exterior siding over the tarpaper. There was neither insulation nor interior covering of the walls, the roof, or the floor… just bare wood. Everything leaked. The worst by far were the floors. There were gaps in the wood planks and there were knot holes. When the wind blew, dust and sand poured into the buildings. The carpenters did the best they could under impossible circumstances, but it wasn’t enough to result in adequately constructed housing, even for barracks (which are by definition Spartan).

This picture of the barracks under construction shows how bare bones and flimsy they really were. Still, the physical inadequacy was just the beginning.

The fundamental problem with the barracks was that they were barracks. Barracks are designed for armies not for families. Each barrack was 20 feet wide and 100 feet long. There were four “apartments,” using the term loosely. Each “apartment” was equipped with a single bare light bulb, a small oil heater, and not much more. There were steel army cots. Upon arriving in Manzanar, each person was given a cloth sack to fill with straw for a mattress. There was no other furniture and there were no partitions. In most cases, eight people were crammed into a 20’x 25′ “apartment.” It would have been bad enough if they had all been members of the same family. But, often there were two families in one “apartment,” or there were unrelated couples in the same “apartment” with a family. Sometimes those couples were newlyweds. What a honeymoon.

“Not only did we stop eating at home, there was no longer a home to eat in. The cubicles we had were too small for anything you might call ‘living.’ Mama couldn’t cook meals there. It was impossible to find any privacy there. We slept there and spent most of our waking hours elsewhere.”

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Child at Manzanar, from “Farewell to Manzanar”

The next two photos are of the barracks reconstructed by the National Park Service.

If you look closely, you can see that the exterior wall “siding” consisted of either 1″x 6″ or 1″x 8″ pine boards. Same for the floor boards. As the green wood dried and shrank, it was also subject to warping and cracking. The exterior doors at the end of the building were constructed of the same pine boards (they admit light, and therefore dust).

“I remember waking up in the morning and being covered in sand. Whenever the wind blew, the sand would come in through the floor.”

Frank Kitamoto, Child at Manzanar, Densho Digital Archives (DDA)

Some folks were handy and fashioned small pieces of furniture. Below, you see a replica of a baby crib that was built by a resident.

You can also see one of the small oil heaters found in each “apartment.” (Note: the suitcase-like device on the right is part of the NPS interactive display).

For some, the “apartments” eventually evolved, with resident-installed modifications that included sheetrock on the interior walls and linoleum on the floors. However, for many with sparse resources the “apartments” remained the same for three years.

Here’s a picture of a gentleman lying on his cot.

“The room was small and there was no furniture (other than cots). We made a table and bench from scrap wood. We made quilts or rugs out of discarded clothing. Nothing was wasted.” (Then, responding to a question about changing over time)…“The apartment stayed the same the whole time we were there.”

Sumiko Yamauchi, Manzanar, DDA

THE WOMEN’S LATRINE…

As if the lack of privacy in the barracks was not enough, the bathroom and shower facilities were housed in military-style latrine buildings. The one shown here is a reconstruction of a Women’s Latrine (there was one for women and one for men in each block of fourteen barracks). In a Manzanar latrine, there were toilets and a communal sink, an open changing area, and showers. There were no partitions and there was no privacy whatsoever. On an average day, 150 people used each latrine.

“One of the hardest things to endure was the communal latrines, with no partitions; and showers with no stalls.”

Rosie Kakuuchi, Manzanar

NPS Brochure, “Manzanar: Japanese Americans at Manzanar”

The photos below show the stark facilities as they were inside the Latrine.

Here was the first row of toilets…

This was the communal sink (trough) and the open changing area for the shower…

Here was the view from the second row of toilets across to the changing area and communal sink…

This was the view into the shower room…

This was the view out of the shower room…

The people who were taken to Manzanar employed many strategies for finding some measure of privacy, including going to the toilet and the shower late at night, or to a latrine that was less frequently used than others.

“Children are amazingly adaptable. What would be grotesquely abnormal became my normality in the prisoner of war camps. It became routine for me to line up three times a day to eat lousy food in a noisy mess hall. It became normal for me to go with my father to bathe in a mass shower.”

George Takei, Child at Rohwer and Tule Lake

In many ways, this story about the latrines is the most shocking of all about the WRA Camps. There is a dehumanizing quality to the latrines, almost as though there was an effort to treat people with greater disrespect than did the incarceration itself. This was done by our government in the name of national security. Done to our fellow Americans.

It felt like an invasion of privacy to take these photos. Still, I think it was necessary to do so…to witness to the scale of the injustice done with the WRA Camps.

NO MEALS AT HOME…

It might have been a place of fond memories of songs and skits were it a summer camp dining hall. It might have been a place of stability were it a military Mess Hall. The first would have been part of a voluntary experience. The second would have been part of a patriotic choice to serve the nation in the context of WW II.

But, it was neither of these things. There was no choice in the matter of eating in a Manzanar Mess Hall. Rather, it was a place where people were compelled to eat food that was mediocre (especially in the beginning), in a setting which was utterly lacking the intimacy of a family meal together.

There was a wide range of reactions to eating in a Mess Hall. It was disruptive and unsettling for families, because it took them out of their routines of eating together. It was liberating for some and enervating for others. Some children found it to be a great adventure, seeking out friends in Mess Halls far away from their own barracks. Some young adults made new friendships or found new love in the Mess Halls. Whatever the reaction, there was the simple reality that the Mess Halls were yet another expression of the absence of choice and the lack of a real home for each person who was taken to Manzanar.

A bit of perspective. There were 10,046 people inside the Manzanar prison Camp. They ate three meals a day, roughly 30,138 meals a day served in 36 Mess Halls…365 days a year. That is about 11,000,370 meals each year, in 36 Mess Halls…about 305,500 each year for each Mess Hall. The Mess Halls were meal factories and distribution centers.

The following pictures are of a reconstructed Mess Hall at the NPS Manzanar site.

The first four pictures are of the kitchen.

Standing in line, waiting to be served, this was the view of what lay ahead.

A fuller view of the kitchen itself.

One of the preparation tables.

A central preparation table.

The next photos show the Mess Hall itself.

The view of the Mess Hall from the serving line.

An NPS exhibit photo, showing apparently unrelated men eating a meal.

An NPS exhibit photo, showing a family eating a meal.

A photo capturing the density of one half of the eating area. The NPS exhibit photo in the background shows that young people occasionally had dances in the Mess Halls.

There were widely varying accounts of the Mess Hall experience. Two impressions are shared below by people who were taken to Manzanar…

“Thursday was always ‘slop-suey’ and Wednesday was always fish (smelt). Smelt is what we used for bait, not for eating.”

Mary Suzuki, Manzanar, Densho Digital Archives (DDA)

(Did you eat together as a family?) “As far as I remember, no. We were always running around to the other mess halls. We never ate together as a family.”

(Did the food get better?) “Yes, when they recruited former chefs from camp people and they taught other camp people how to cook.”

(What was your favorite meal?) “Fried rice with an egg on top.”

George Kiyo, Child at Manzanar, DDA

THE IMMENSITY OF PLACE…

When I first drove to Manzanar in the winter, I was struck immediately by the sheer immensity of the place. The Owens Valley is a vast remote configuration; the plane of the valley floor seems to go on forever. On the western edge there is the southern Sierra Nevada. Topping it all is an intensely blue sky. The tableau suggests a limitlessness…almost as though there was no end to the captivity.

Walking out on the site in winter, it is cold, the air is dry, and the land seems almost devoid of life. It was a harsh place to send 10,000 urban dwellers mostly from coastal California.

There is a deep incongruity here…that this place of immense beauty and wildness could also be a place of captivity.

Walking out in Manzanar in the spring, one sees that life is coming back to the place. In the midst of the vastness, one sees the wildflowers, leaves on the trees, and the wild shrubs sprouting their light green. There is a bit of color where there had been almost none. It is the color of life… Walking around, I feel that the people who were taken to Manzanar were aware of nature’s life cycle there. Deep in my heart, I hope that this life cycle in which they lived offered some measure of comfort.

There was an outdoor theater in the northern part of the Camp. Here you see the view from it, looking northwest to the Sierra. I imagine that it gave a sense of the larger beauty of things. The raw beauty and power of the high desert and the southern Sierra Nevada reflected the appreciation of beauty, as well as the tenacity of the people who were taken to Manzanar.

“I can now understand how an eagle feels when his wings are clipped and caged. Beyond the bars of his prison lies the wide expanse of the boundless skies, flocked with soft clouds, the wide, wide, fields of brush and woods—limitless space for the pursuit of Life itself.”

Kimi Tambara, Minidoka, from the National Archives

PLACES OF BEAUTY – PLEASURE PARK

In a place faraway from home…where people were taken against their will and in utter violation of their Constitutional rights…still in that place, there were some who sought to make places of beauty. It was a tenaciously human act of creation. The largest such place in Manzanar was created by Mr. Nishi.

Kuichiro Nishi, a nursery owner and garden designer from Los Angeles, led the creation of what was first called Rose Park, then Merritt Park, and finally Pleasure Park.

“With its visually striking rock gardens, ponds, rustic bridge, gazebo, and diverse plantings—including roses that Nishi cultivated—the park became a sanctuary of tranquility for the Manzanar community.”

Manzanar Committee

Careful attention to detail is about more than precision. It is also about care for others. More precisely, it is taking care of the minute detail of design and construction so people will be able to appreciate and experience a place without thinking about it.

Here is a spot which seems like a portal to the world outside.

“Sometimes in the evenings we could walk down the raked gravel paths. You could face away from the barracks, look past a tiny rapids toward the darkening mountains, and for a while not be a prisoner at all.”

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Child at Manzanar, from Farewell to Manzanar

HONOR AND SACRIFICE…

This Memorial Day weekend, we remember the honor, the courage, and the sacrifice of Americans of Japanese ancestry who served in the American armed forces during World War II.

As the United States entered WWII, there were many American politicians, columnists, broadcasters, and military officials who questioned the loyalty of Americans of Japanese ancestry. Fueled by the venomous rhetoric of Lt. Gen. DeWitt and columnist Walter Lippmann, some politicians went so far as to say that Japanese Americans were disloyal as a group and a danger to American national security. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

Men and women volunteered from the Camps and from Hawaii to serve in the military. The Densho Encyclopedia estimates that approximately 33,000 Japanese Americans served in the Army during World War II and/or in the immediate aftermath with the occupation forces. Of these, an estimated 6,000 people served in the Military Intelligence Service and 18,000 men served with the Army’s 442nd Regimental Combat Team. [From, Densho Encyclopedia]

The first two women enlistees, [from Dept. of Defense Archives]

It is difficult to find an exact number of Japanese American women who served in the armed forces during WW II. I have not found a reliable number I can share. However, the following illustrates the range of military occupations of the women who did serve…

“…many second-generation Japanese American (Nisei) women wore U.S. military uniforms. Nisei women contributed to U.S. war efforts in various ways, including as army personnel, military nurses and doctors, as well as photo interpreters and linguists with the Military Intelligence Service. The history of Nisei women in the U.S. military began when the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) and the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) started to accept Nisei women in February and November 1943, respectively. The backgrounds, experiences, and struggles of Nisei women who served in these corps have just started to be revealed in the last couple of decades by scholars.” [from, “Japanese American Women in Military” in Densho Encyclopedia]

At the conclusion of training, [from Densho Encyclopedia]

Men served with courage and distinction in the U.S. Army 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Suffering tremendous casualties in the European theater, the 442nd was one of the most highly decorated units in the war. One reliable source estimates the total number who served in combat at between 7,500 and 8,500. I have been unable to find more definitive statistics.

Known by it’s bravery and toughness, the 442nd had the motto, “Go For Broke.” This painting, which recreates a battle of 442nd infantrymen against German tanks, gives an inkling of what the motto reflected. [Source: U.S. Army Center for Military History]

In little more than one and a half years of battle, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team was involved in five major campaigns in Europe.

On the march toward battle, [White River Valley Museum]

Rescuing the “Lost Battalion,” [Japanese American Museum, San Jose, CA]

The men of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team were awarded an extraordinary number of individual military honors:

- 21 Congressional Medals of Honor

- Over 4,000 Purple Hearts

- 29 Distinguished Service Crosses

- 588 Silver Stars,

- More than 4,000 Bronze Stars

Units of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team were awarded six Distinguished Unit Citations, with one awarded in person by President Harry S. Truman.

President Truman and the 442nd [National Museum of American History-Smithsonian]

During the one and a half years of battle, the 442nd sustained terrible casualties:

- Over 700 killed or missing in action

- Over 3,700 wounded in action

[Source: Densho Encyclopedia]

“…I had the honor to command the men of the 442nd Combat Team. You fought magnificently in the field of battle and wrote brilliant chapters in the military history of our country.”

“They demonstrated conclusively the loyalty and valor of our American citizens of Japanese ancestry in combat.”

General Mark W. Clark

“All of us can’t stay in the [internment] camps until the end of the war. Some of us have to go to the front. Our record on the battlefield will determine when you will return and how you will be treated. I don’t know if I’ll make it back.”

Tech. Sgt. Abraham Ohama, Company “F”, 442nd RCT,

Killed in Action 10/20/1944

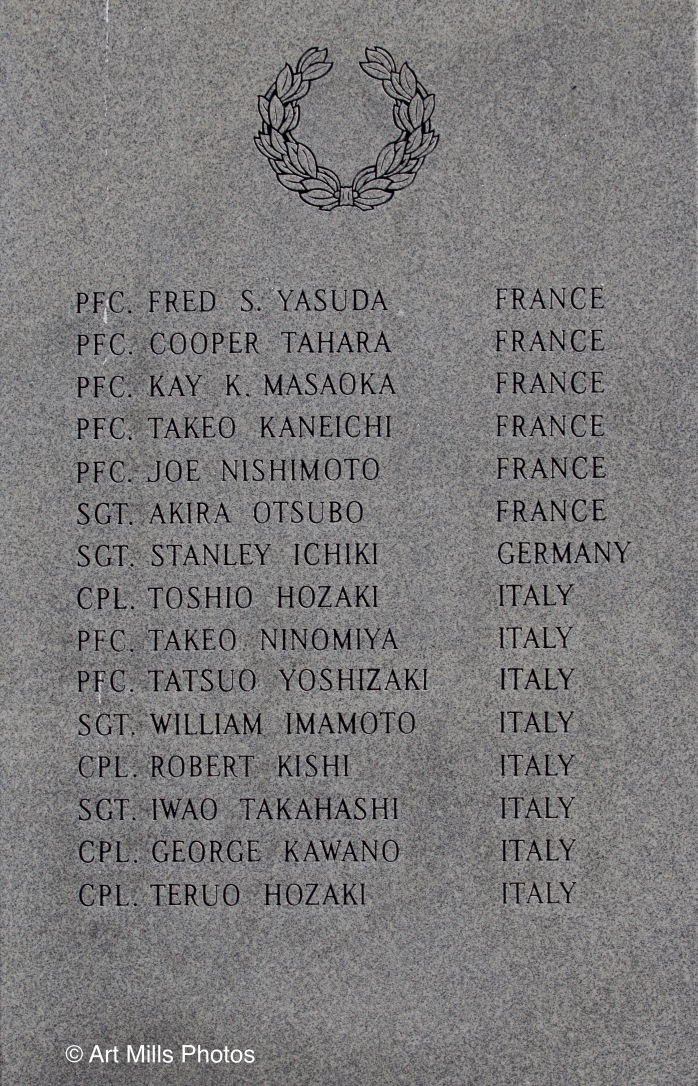

Of course, Manzanar had its own group of young men who volunteered to serve in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Four of these young men were killed in action while fighting with the 442nd:

Pfc. Frank N. Arikawa – July 6, 1944

Sgt. Paul T. Kitsuse – November 2, 1944

Pfc. Sadao S. Munemori – April 5, 1945

Sgt. Robert K. Nakasaki – April 5, 1945

“Manzanar has its first gold star mother. We had dreaded the day when some family in Manzanar would receive the fateful telegram….”

[Manzanar Free Press article on Pfc. Frank Arikawa’s death]

STONES AND DUSTY FOOTPRINTS…

The people who were taken to Manzanar retained great human dignity and a profound love of natural beauty. One expression of this was the placement of small clusters of stones near their barracks. This cluster is near where Building 5 in Block 28 was once located. Jeanne Wakatsuki’s father placed a cluster of stones near their “apartment” entrance in the new barracks they moved into in 1943.

“Whitney reminded Papa of Fujiyama, that is it gave him the same kind of spiritual sustenance. The tremendous beauty of those peaks was inspirational, as so many natural forms are to the Japanese (the rocks outside our doorway could be those mountains in miniature). They also represented those forces in nature, those powerful and inevitable forces that cannot be resisted, reminding a man that sometimes he must simply endure that which cannot be changed…

What had to be endured was the climate, the confinement, the steady crumbling away of family life.”

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Child at Manzanar, in Farewell to Manzanar

Walking around Manzanar, I was struck by how many people had walked on the same paths. Most had walked with great courage, born of an injustice so vast and so incomprehensible. Sorrow was a companion for many. Beauty and wisdom were a constant presence.

“Papa’s life ended at Manzanar, though he lived for twelve more years after getting out. Until this trip I had not been able to admit that my own life really began there.”

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Child at Manzanar, in Farewell to Manzanar

I am grateful to walk on this sacred ground, to hear the stories, and to know that I will be back.

OVERCROWDING AT TULE LAKE…

Tule Lake was overcrowded from the start. It also suffered from federal government mismanagement for the duration. This sorry combination was one of the factors that led to major problems at Tule Lake, to its becoming the maximum security prison camp of the WRA Camp system, and to its being such a complex place to understand.

The National Park Service (NPS) has recreated barracks rooms, using an old barracks building which they reclaimed from a land owner in the area. It is on the site of the present NPS Tule Lake Unit, a site shared with the World War II Valor Museum on the Modoc County Fairgrounds.

To get an idea of what I mean by overcrowded, take a look at this image of the inside of a barracks “apartment.”

This small, open room was designed for a family of four who used the room as “home.” It was 16 feet x 20 feet. Notice the wall on the left hand side…in theory, it provided privacy. But, note that the wall only went to the rafter line. Above that, was open space (it was that way for all of the interior walls in the 100 foot long barracks). There was no privacy.

It is difficult to imagine a family living here. It is not a home in any real sense. The families must have been deeply shocked to be shoe horned into one room. A family of four was squeezed into a one room “apartment” that had 320 square feet (s.f.). In 1942 California, a modest sized house for a family of four would have been 1000 to 1200 s.f.

Let’s put this in a WRA context. All the WRA Camps were crowded, with too many people living in too little space (the WRA planned for 32 people to live in each 2,000 s.f. barracks building). Think about that in terms of your current home. Think about it also in terms of what the Camp was originally designed for and how many people actually lived there. The Tule Lake Camp was initially designed to house 15,000, but housed nearly 16,000 people. Then, it’s capacity was expanded to 16,000, but 18,789 came to live there. Only one other WRA Camp, Manzanar, exceeded its design capacity. Manzanar was designed for 10,000 and had 10,046 living there at its maximum occupancy. Most other Camps operated at significantly below capacity, while Minidoka operated at 93% and Amache operated at 91%. There was an appalling over crowding at Tule Lake right from the start. As you will see, that led to major problems.

“We saw all these people behind the fence, looking out, hanging onto the wire, and looking out because they were anxious to know who was coming in. But I will never forget the shocking feeling that human beings were behind this fence like animals [crying]. And we were going to also lose our freedom and walk inside of that gate and find ourselves…cooped up there…when the gates were shut, we knew that we had lost something that was very precious; that we were no longer free.”

Mary Tsukamoto, from The National Museum of American History

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT…

There are so many buildings and structures from the Tule Lake WRA Camp that are still there, intact, on the site… hidden in plain sight…

This is the Carpentry and Paint Shop. The building has been beautifully restored by the National Park Service (NPS). Since it is right by State Highway 139, this building may become the eventual NPS Vistors Center for the National Monument.

Nearby is the old Camp Motor Pool. Located next to the Caltrans Maintenance Yard, these two motor pool buildings were used by the County for a time. Now, the buildings are within the 31 acres that is owned by the NPS.

Farther down Highway 139, one finds a collection of five large storage buildings from the Camp. There is a railroad spur along side them, dating from the days of the Camp. I’ve captured the three largest of the buildings…

Massive in size, they are in good condition, and have been in constant use since the time of the Camp.

The Federal government sold the five buildings to a local agricultural business shortly after WW II. Apparently, discussions have been under way to return the buildings to NPS ownership. They would be a huge addition to the Camp site and to the NPS interpretation of it. There are two private residential neighborhoods on the former Camp site. One is not far from these storage buildings. One is back where we started today’s part of the trip.

Just east of where we started at the Carpenter Shop, is the location of the Camp’s Military Police (MP) Compound. In this area, we see a small neighborhood. The neighborhood lives on the same streets that were there for the MP battalion. Most of the homes in the neighborhood are clearly made from the Camp’s MP barracks.

Here are photos of three of those homes…

Earlier, I mentioned Camp infrastructure… This twenty five cent word is part of our country’s political discourse. Never a glamorous subject, infrastructure was essential to the operation of this prison Camp full of 20,000 people. The Tule Lake WRA Camp required streets, power, water, and of course a sewer system. The sewer pipes at this Camp were connected to a structure invented by a German engineer, Dr. Karl Imhoff, in 1906. Called an Imhoff Tank, it was commonly used in the U.S. through the late 1950s. The one at the Tule Lake WRA Camp served the needs of the 20,000 people there and was later used by the Newell County Water District, perhaps into the very early 1970s.

I spoke with a man who farmed for twenty years on land in the eastern portion of the Camp (just east of the current Tulelake Airport). He said that occasionally, the Water District would flush the system and the lids throughout the area would pop up, always a startling moment.

This is the Imhoff Tank that was located on the northern edge of the Camp. It was connected to large effluent beds and a sludge bed. There was a second Imhoff Tank built when the Camp was expanded, but it was never put in use.

The Tule Lake WRA Camp… is in the middle of nowhere. That’s true for most of the WRA Camps. This is in part due to site selection criteria that included: ease of acquiring federal ownership or control of the land; suitability for agriculture; availability of water; a large amount of land; and, distance from the West Coast population centers. Now as then, it is easy to miss or to forget that this huge site is even there, let alone that over 18,000 Americans (most of them U.S. citizens) were brought here against their will and without due process. The remote location makes it even more difficult for us to rebuild our collective memory and conscience.

My journey continues… Next, I’ll look at some of the remnants of the Camp that are visible if one digs just a little bit.

MYSTERIES…

One of the most interesting things about the Tule Lake Camp concerns things that are NO LONGER VISIBLE…or, REMNANTS of things that are long gone… There are Mysteries to unpack and Stories to tell.

Remnants of buildings and structures can be found all over the site of the Tule Lake WRA Camp. Some are in plain sight…if you recognize what they are. Others are more illusive. Often, you need to cross a fence in order to find them.

Come with me on this part of the journey…this pursuit of mysteries and stories.

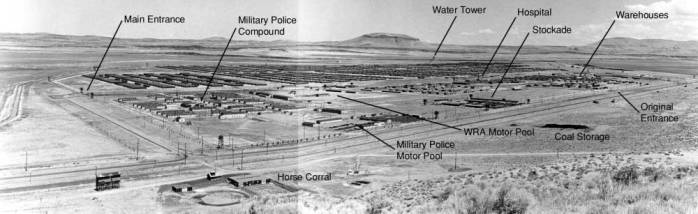

This is a wide view of the Tule Lake Camp in 1943. Roads filled the Camp in a city-grid pattern, connecting the barracks blocks and the administrative areas. The roads were everywhere. [Source: Library of Congress]

If you wander, ignoring the fences, you’ll find a patchwork of the old roads. Here is the remnant of a road heading East, near the airport.

Somebody doesn’t want you to wander out here. The Tulelake Airport folks, with the apparent backing of the FAA, are planning to erect an eight foot fence out there. It would cut off access to about half of the former WRA Camp. Some people suggest it is a matter of national security. What?… there is no one out there… there are hardly any airplanes taking off or landing. In four days of visits (weekdays and weekends), I never saw one airplane using the airport. Is the fence to stifle curiosity and memory? When I wander out in these fields, on these roads, I imagine the hundreds of thousands of interactions that took place among the people who were taken to Tule Lake. Shouldn’t we be about discovery instead of covering things up?

The remnants of the roads are there, but look in the first picture in this post… it is filled with barracks. Where did those barracks go? There was housing for 16,000 people in that picture. Where are they now? It’s actually a mystery that is easily solved. After WW II, the federal government decided to give a group of returning veterans the use of the barracks and the agricultural land from many of the WRA Camps. In the case of Tule Lake, the government conducted a lottery for returning GIs. The winners each received 80 acres of former camp land for a farm, and the right to 1 1/2 barracks for a home and an out building. It was the last use of the Homestead Act (from the post-Civil War era).

In my previous post, I mentioned meeting a man who farmed for 20 years on former Camp land. He had purchased his 80 acre farm and house from a WW II veteran who had homesteaded the land and who was retiring from farming. The man I met lived in a house converted from one of the Camp barracks. Mystery solved… By the way, that man expressed the hope that the NPS would find one or two of the barracks and transport them back to the Camp for restoration.

Across another barbed wire fence, on Tulelake Airport land, I found this foundation for what was called a Bathhouse at the Tule Lake WRA Camp. At the near end, are two rows of holes in the concrete floor. These were for the toilets, which were separated by a three foot high partition. At Tule Lake, there was an efficiency of construction in that each Bathhouse building had a men’s latrine and shower at one end and a women’s latrine and shower at the other, with a boiler room in the middle.

The next photo shows a linkage of the underlying Camp infrastructure.

This telephoto image shows the foundation of a bathhouse with the Imhoff Tank sewage treatment facility in the background. Each Block of 14 barracks buildings was served by one Bathhouse building. There were at least 74 such Bathhouses in the Camp, not including those for the MP s and administrative staff. They were all connected to the Imhoff Tank via sewer pipes. I have no idea where those buildings went, but I do know where the underlying pipes are…in the ground. Let’s go back above ground to look at one of the most prominent aspects of the Tule Lake WRA Camp.

This is a 1942 technical drawing for the design of the Guard Towers at Tule Lake.

[Source: the National Archives]

Tule Lake started out with 6 of these towers. When the Camp was turned into a maximum security prison camp for people who were supposedly disloyal to the United States, the number of guard towers increased to 28.

This is a remnant of one of those 28 towers. I found it in the Camp Motor Pool area, behind the Caltrans Maintenance yard. Oh, what range of emotions just the sight of such a tower must set in motion. There was surely mix of veterans and rookies who manned these towers as armed guards. For most people in the Camp, the towers were stern reminders that this was a prison Camp. For some of the kids in the Camp, the towers represented a chance for high stakes playfulness…

“…they had a main fence here, they had a little fence, a warning fence, and what we used to do is a bunch of us guys go there, the guard towers every three hundred feet, so that’s we used to do. Run up by that warning fence, we’d stand there and the MP would get excited, then we’d give him a one-finger salute and we’d walk… [laughs]. But the best thing is that, we used to, another thing, we used to go over there and jump on the other side, “We’re just going to the other side of that fence,” because it’s low, you could jump over there. We’d go over there, and boy, the MP get by, and pretty soon we’d see the dust flying and we knew a jeep or somebody coming with a jeep, so we’d just go on the other side, and once we got on the other side, we scattered. Hell, they didn’t know who in the hell we were. We all look alike, so they didn’t know. But if you’re incarcerated, you do anything to get after the authority as per se.”

Taketora Jim Tanaka, age 16 in Tule Lake

The worst remnant involves a desecration. It is a mystery that I have been unable to fully resolve.

This photo was taken near the Southwest corner of the Camp. It is where the Camp cemetery was. What remains is an area that was obviously excavated… Barbara Takei and Judy Tachibana have written the most accessible book about Tule Lake, entitled “Tule Lake Revisited: a brief history and guide to the Tule Lake Concentration Camp Site.” The authors suggest that the former cemetery was dug up with bulldozers (human remains and all) and used as fill for construction projects elsewhere in the area [Tule Lake Revisited, p. 40]. Most of the 10 WRA Camps have small cemeteries with monuments to those who died in captivity. Here there is nothing. What exactly happened? Where was the construction site to which the earth and remains were taken? Who decided to do this? What local or federal government official allowed this to happen or approved the action? What dark motivation drove this act of desecration? These questions cry out for an answer.

The Newell Homstead Market is out of business. It is a sprawling, old building on State Highway 139, in front of where the Tule Lake Camp Hospital was. What is not apparent is that this old building served as the Recreation Center for Tule Lake Camp staff.

Prisoners at the Tule Lake Camp built the rock fire place that fronts the building.

So, most of the mysteries are solved. One requires some more answers. All of the remnants lead to more questions: What will become of this area? With so much undeveloped land around the former site of the Tule Lake Camp, and with so many remnants in place or close by, how much historical restoration of the Camp will the National Park Service be able to accomplish with its limited budget?

There is one more stop on my visit to the Tule Lake WRA Camp. Next time, we’ll look at the Stockade and the Jail that were a central part of the conversion of Tule Lake from a “Normal” WRA Camp into the maximum security prison camp for the the WRA Camp system.

A WRA MAXIMUM SECURITY PRISON…

This photo from the California Military Museum shows the Stockade front and center at Tule Lake. The jail, which was built shortly after the photo was taken, was adjacent to the Stockade compound. Both feature heavily in the rest of this story.

Tule Lake started out as one of the 10 regular WRA prison Camps. The WRA leadership quickly mishandled (and in some cases abused) the process of questioning the 110,000 people who had been taken to the WRA camps about their loyalty to the United States. This may have been driven by a U.S. Government assumption that Japanese Americans were not loyal.

The whole questioning process was basically an unmitigated disaster. The questionnaire that the government used was put together without any consultation whatsoever with Japanese American leaders. Even for simple questions this created difficulties. For questions 27 and 28, the process created terrible problems:

- Question number 27 was especially problematic for second generation men. It asked if they were willing to serve on combat duty wherever ordered. This, despite the fact that their families were imprisoned without due process.

- Question number 28 was deeply problematic for first generation men and women. It asked individuals if they would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. It is Important to Note: 1) a racially based federal law prevented first generation Japanese American men and women from becoming U.S. citizens; therefore, 2) a “Yes” answer could easily make them persons without a state (a dangerous position in the middle of a world war), many of whom were being threatened with deportation.

- The questionnaire allowed for only “Yes” or “No” answers to the loyalty questions.

- A “No” answer meant that the person was branded “Disloyal.”

- A “Yes” answer qualified by comments about the injustice of the WRA internment was also branded “Disloyal.”

- The two questions were poorly explained in several of the Camps (including Tule Lake). There was considerable pressure to comply, and there was substantial resistance to the entire process.

- The two questions weren’t really questions…they were demands masquerading as questions.

- Beyond this, the questions were asked of people who had been imprisoned without charges or a trial. Any normal person in this circumstance would have had reservations about the questions and would have been reluctant to just blindly answer “Yes” as the government demanded.

[Source: Densho Digital Encyclopedia]

The loyalty questioning could have been the stuff of satire and late night comedy. However, it was no joke. It was yet another tragic aspect of the process of taking Americans to the WRA Camps.

In July 1943, after the loyalty questioning debacle, the government decided that it needed a maximum security prison within the WRA Camp system for all of the “Disloyal” Japanese Americans. The Government chose Tule Lake. Tule Lake WRA Camp became that maximum security prison and was renamed “The Tule Lake Segregation Center.” A battalion of U.S. Army Military Police was brought in, complete with armored vehicles, to maintain order at the prison Camp. This set in motion a huge movement of people between the WRA Camps.

- “Loyal” people in Tule Lake were shipped out to other WRA Camps.

- “Disloyal” people from the other WRA Camps were brought to Tule Lake.

- Some people in Tule Lake who were “Loyal” elected to remain in Tule Lake in order to be close to family members who were “Disloyal.”

- Eventually, 18,789 Americans came to live in Tule Lake, in a prison camp designed for 16,000 people.

There was no due process if you were branded disloyal, were sent to the Stockade, or were put in the Jail. An arbitrary decision, by some combination of civilian and military authorities at Tule Lake, sent one to the Stockade or to the Jail. There was never any explanation. There were no hearings or trials. People just ended up behind an additional row of barbed wire and possibly in a concrete blockhouse-style jail.

“…then as I recall, from one side of the camp the military came with a list of people and the administration came from the other side, and they picked up all the people on that list. And my brother’s name and my name was on that list. Why, we don’t know.”

K. Morgan Yamanaka, Tule Lake [Source: Densho Digital Repository]

This is a picture of the jail now. It is a concrete blockhouse, built by prisoners in the Camp. Several years ago, Caltrans built a steel cover for the building to prevent further deterioration of the concrete.

This is a picture of one of the jail cells. The steel gate, steel beds, and toilet have been removed.

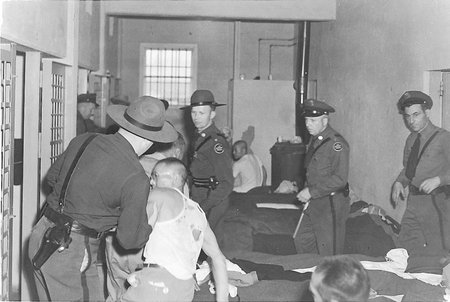

This photo shows the same cell crammed full of inmates in late 1943 or early 1944. Conditions were unbelievably cramped. The Jail was designed for 20 prisoners; 100 were crammed into the block building.

[Source: National Archives]

This photo shows the guards manhandling a prisoner. You can see that people were sleeping on cots in the corridor.

[Source: The Tule Lake Committee]

This is an image of one of the steel cage structures that enclosed the cells. The steel cage pieces are presently in storage awaiting restoration of the Jail.

[Source: National Archives]

The Stockade was located on the Western side of the Camp. The Stockade compound included:

- An open area surround by a high barbed wire fence.

- Two barracks buildings.

- A mess hall.

- A latrine building.

The Stockade was designed for 100 prisoners; 400 were crammed in there.

This is the stockade under construction in 1943. [Source: Densho Digital Repository]

Terror was a frequent visitor to the Stockade. It often involved late night harassment by the Military Police. Here is Morgan Yamanaka talking about midnight raids at the Stockade Barracks…

“As a matter of fact, one of the times in my life I was actually scared was when, one of those midnight raids — are you familiar with Thompson sub-machine gun, the round cartridge? That Thompson machine gun was aimed at my belly by a young soldier who seemed to be shaking because he was scared. Well, I know something about arms because in martial arts we were studying arms. His trigger finger was on the trigger. Well, if you’re shaking like this the damn finger could… and I’m aware of this, so I think that was about the only time in my life I was physically scared.”

K. Morgan Yamanaka, Tule Lake [Source: Densho Digital Repository]

The conversion of the Tule Lake Camp to a maximum security prison was the harshest feature of the WRA Camp system. With its methods, the Tule Lake Prison Camp magnified the violation of due process that was inherent the imprisonment of 110,000 Japanese Americans in the WRA Camps in the first place. It was a dark, enduring chapter.

“A Place of Solace…”

This is a photo of Castle Rock, and its peninsula. It is the most prominent nearby geographic feature and was visible from anywhere in the Camp. Castle Rock provided a place of solace for many people who were imprisoned in Tule Lake. Up until the summer of 1943, when Tule Lake became a maximum security prison, people from the Camp were able to walk up the mountain at specified times. It became a place of religious observation and spiritual meditation.

Tule Lake was a complex prison camp, and I have only scratched the surface. I will miss being there, looking for stories, solving mysteries. Hopefully, I’ll be back, perhaps at the next remembrance gathering there.

THE REMAINS OF THE JEROME, ARKANSAS WRA CAMP…

The Jerome WRA Camp was about 130 miles southeast of the city of Little Rock, Arkansas. There is almost nothing left of the camp that once held 8,947 Americans of Japanese ancestry for nearly two years. When the camp was built, the land was wooded swampland which local farmers had tried to convert to farmland. It is now part of large scale farmland, surrounded by forests, bayous, a short distance west of the Mississippi River.

The site of the Camp is on the east side of US 165, about 18 miles south of McGehee, Arkansas. Approaching, you need to remain alert, or you will drive right by the granite monument that commemorates the Camp…

Here is the monument on a small square of land, just off Highway 165.

The next four photos offer different views of what was the central residential part of the prison Camp site. The Jerome Camp was about 10,000 acres in size, much of which was used for farming during the two-year life of the Camp. The residential part of the Camp was about 500 acres.

From the monument, looking to the North, on the edge closest to Highway 165.

Looking to the East from the monument, toward the back of the property. The residential area would have extended all the way to the tree line.

Looking to the South from the monument, toward the end of the residential area, also along the edge of Highway 165…

This is what remains of the towering smoke stack of the Camp hospital, located on the Southern edge of the residential area of the Camp.

“…the camp itself was located in a kind of swamp, a cleared out swamp. Because around the camp was a pretty high level… six or seven foot high levees, you know. And this area that we were in evidently, they must have drained it or something, you know. And then that’s where they built it because these were built off the ground, three or four feet, three feet maybe. Because when it rains in Arkansas, it rains like… like no tomorrow, you know, it just floods. And then on one side, the side next to the road, where the main road is, and the railroad tracks, there was no levee there but on three sides there was a levee. And then within the camp, within the block itself, there was a slight levee with a channel dug so that the water could flow out.”

Osamu Mori, Jerome (from Densho Digital Archive)

ANOTHER GLIMPSE INTO THE PAST…

This picture is of a display in the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, part of an exhibit entitled, “Education in Exile.” The Center is a unit of the Central Arkansas Library System, and is located in downtown Little Rock, at 401 President Clinton Avenue.

It is possible to gloss over the experience of people in the Camps. That would be one way to observe the photo above. I think, however, that the preceding photos show the extent to which people will go to make the best of a terrible situation. The woman at the table and whoever made the furniture were providing a measure of order and hope for the members of their family.

ROHWER WRA CAMP, TODAY…

To get to Rohwer, you drive through the countryside north of McGehee for about 12 miles . As you come upon the hamlet of Rohwer, you’ll drive alongside a levee and a dense row of trees on the left hand side of the road, and soon you’ll see a small sign indicating the Rohwer Camp cemetery.

Crossing over the levee (which is an old railroad bed), the first thing you notice is water on the left.

Being a West Coast guy, I immediately look for alligators.

Then, you look straight ahead and see this…

The visitors kiosk explains the basic Camp layout and points the way ahead to the cemetery.

It’s a cold morning, but I set out walking toward the cemetery.

This is a monument to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an all Japanese American unit in the 5th Army.

This second monument was built later.

Sam Yada, originally imprisoned in Rohwer, remained to live the rest of his life as a farmer in the area. Sam worked effectively with local people and various government and academic entities to preserve the cemetery.

The portion of the cemetery in the photo below includes those who died during their imprisonment in the Rohwer Camp.

Continuing to walk alongside the cemetery, I look toward the back end of the Camp’s residential area.

About halfway from the Kiosk at the front of the Camp, I come upon this interpretive board. In the background is the towering smoke stack from the old hospital.

A telephoto shot of the smoke stack from the same spot.

Turning back toward the kiosk, you can see the front end of the Camp’s residential area.

Back my starting point at the kiosk, I turn to take a picture of the Northern side of the Camp. The Camp’s residential area extended just beyond the treeline.

Standing at the same spot, I turn West, capturing the size of the Camps’ 400 acre residential area. Throughout the Rohwer Camp site, the soil is rich. Even though the surrounding land was drained for the Camp, and drained by farming operations after the camp, there is a lot of water on the ground. It explains why the land was available for a Camp in the first place. It also makes me appreciate how much work the Japanese Americans did to make the Camp livable and the land farm-able.

Finally, I was fortunate to spend a portion of the morning with a mother and daughter from the area. A mutual friend introduced us. They graciously walked the site with me, showed me the surrounding area, and explained how the preservation efforts had happened. I deeply appreciate their hospitality.

SAYING GOODBYE TO ROHWER…

Boarding the train to go back to Sacramento. [Source: unknown]

A mother, whose four sons served in the Army in WWII, says goodbye as she heads back home to California. [National Archives]

“As the radio spokesman announced…that the West Coast was being re-opened, we couldn’t believe it, but we listened tensely… Yes, I really feel excited, but how do I know how my neighbors will treat me when I get back? I surely hope they will treat me like they did during the pre-war days, but you have to expect a few of them to be prejudiced…”

Herbert Yomogida, Rohwer High School

THE MUSEUM AT MCGEHEE: A LITTLE JEWEL BOX…

McGehee, Arkansas is the nearest city to the Jerome and Rohwer WRA Camps, roughly halfway between them. In 1942, McGehee had a population of about 3,600. The two Camps had a combined population of 16,972. McGehee is still a small city.

In the middle of town, is a little jewel box… a small museum dedicated to the Jerome and Rohwer Camps. Filled with gems, the museum has a collection of photos, quotations from Camp prisoners, and artifacts from the sites. Two curators staff the museum. Remaining in close contact with Japanese Americans who were in the Camps, the curators obviously work to sustain a collection that carefully reflects what took place at the two camps.

“The next order was that we were going to be moved to Arkansas. We had to pack up our belongings again and crate them. This was another sad movement of my life. We came on the first crew. We came by the southern route. It took us three days and four (nights). We were in Rohwer, Arkansas at five in the morning.”

Hiroshi Ito, Rohwer

This exhibit includes photos of some of the people taken to Rohwer.

They have several artifacts on display.

A small box which held some of the possessions the Utsumi family (family no. 26514), who were taken from Stockton, CA to Rohwer.

Recently recovered in a field on the Rohwer site.

A small figurine recently recovered at the Rohwer site.

The care and concern of the museum at McGehee is profoundly touching. In the middle of a remote, rural part of America, men and women work daily to help others remember. Respectfully, they work to keep the memories alive.

GILA RIVER: OPPORTUNITY LOST…

This is a photo of the monument found on a hill in the Butte Camp portion of the former Gila River WRA Camp. [Source: Unknown]

Consistent with its general practice, the Gila River Indian Community withheld permission from me to visit the site of the former WRA Camp and to take photos for this blog. Although I at first received written approval for a visit, when someone higher up realized that I would be taking photos for the blog, I was required to apply for a media permit and was subsequently turned down and refused the chance to visit.

Respecting their decision, I only visited the Huhugam Heritage Center, taking no pictures. I did not go out to any of the former WRA Camp locations.

Given the historic offense of forcing the WRA Camp upon the Indian Community, I understand their apparent reluctance to open the former Camp site to most visitors. The primary exception to their policy is for former internees or their families.

One consequence of their exclusionary policy is that a major opportunity is lost.. The Gila River Indian Community is on the edge of Phoenix, Arizona, only minutes from the Sky Harbor International Airport.

The Community has created an utterly beautiful Huhugam Heritage Center. The Community describes it this way: “On January 24, 2004, the Gila River Indian Community opened arguably the nation’s finest tribal facility for the preservation and display of important cultural artifacts and art.” The Center serves as: “a climate-controlled repository for prehistoric and historic artifacts, cultural materials and vital records…; a museum to display these materials to the public…; a center for research by tribal members…; and, a space to exhibit traveling art and history shows…”

The Huhugam Center lives in the midst of an obviously thriving Gila River Indian Community economy. The Community receives thousands of visitors each year to its hotels, golf courses, businesses, and historical/cultural resources.

Lost is the chance to more fully educate visitors about injustice and resilience. There was a double injustice perpetrated in the creation of the Gila River WRA Camp: the imposition of the camp upon the Community, over the objections of the community leaders; and, the imprisonment of thousands of Japanese Americans in the Camp, without Constitutionally required due process. Beyond this injustice, both peoples have profound stories of resilience to share.

My hope is that the Gila River Indian Community will eventually work with the interested Japanese American groups to carefully build a visitors center that will display this chapter of history.

POSTON PILGRIMAGE I…

This April, I had the privilege of visiting Poston during the Poston Pilgrimage. The Pilgrimage is organized by the families of people who had been imprisoned in Poston. The organizers come from Los Angeles, Fresno, and Sacramento; people come to the Pilgrimage from all over America. This year, the outdoor part of the Pilgrimage started on the Camp site at the Poston Memorial Monument.

Check out the Google Maps link below… When you do that, you’ll see an interactive, aerial image of Poston, AZ, focused on the area of Poston Camp I. It is the farthest north of the three Camps at Poston. If you move the map around, you’ll see the site of the Poston Memorial Monument (on Mojave Road). Slightly north-west, you’ll see the two acre site of the Poston historical work (on Poston Road).

Poston on Google Maps (Zoom in and out to get the full context)

The following pictures show people gathering at the Monument on April 7, 2018.

Official photographers preparing for the ceremony of the day… Family members who dedicated commemorative bricks were about to come up to visit.

Marlene Shigekawa, Project Manager of the Poston Community Alliance, welcomes the pilgrims.

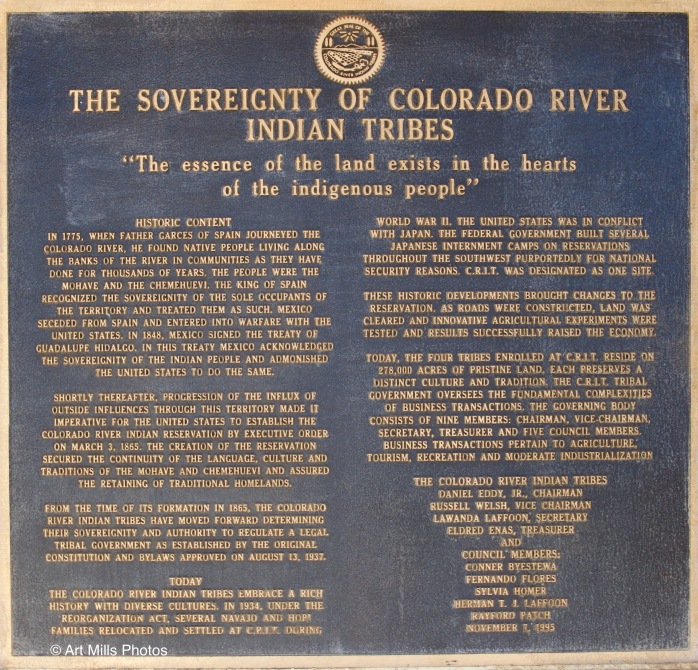

A tribal land use official telling how the tribes and the families of the former internees worked together to build the monument.

Listening to Miss Indian Arizona extend a welcome.

The Tribal Chairman talks about the solidarity of the Indians and the Japanese Americans.

Then, the people went up to the monument, passing by the Monument’s Kiosk…

Pilgrims on the move…

Next up, Poston Pilgrimage II. We’ll look at the site where the Poston Community Alliance and the Colorado River Indian Tribes are working together to create a visitors center and historical site.

POSTON PILGRIMAGE II…

Just across the highway from the Monument, on Poston Road, is a parcel of land that the Poston Community Alliance is working to turn into an active historical site. This is where the second part of the Pilgrimage took place. We were all bused to the grounds and then set free to tour the area, with folks available for interpretation. Dianne Kiyomoto, one of the leaders of the Poston Community Alliance, graciously explained what was there.

The Colorado River Indian Tribes donated 3.7 acres for the “Poston Restoration Area.” The Camp 1 Elementary School at one time occupied the two acres. The buildings (built by the internees out of un-reinforced adobe bricks which they made by hand) were later used by the Tribes (who added the concrete walkways). The Poston Community Alliance (former internees, their families, and friends) and the Colorado River Indian Tribes will work together to develop the site as a historical resource.

Here are pictures from the Pilgrimage to the Camp site.

Pilgrims abound!

This former school building will become the Visitors Center.

This barracks will be restored to show how people were housed at Poston.

Walking the length of the site…

In the center of the historic restoration site looms the remains of the Camp 1 Elementary School Auditorium. The Poston Community Alliance hopes to complete some form of restoration. On the Pilgrimage, it was a magnet, with people exploring inside and out what was an important, central feature of the Camp.

Exploring the interior.

Continuing on…

Reflecting…

In the end, all Pilgrims were left to pause, to reflect upon their past, their experiences, and what they would bring forward with them from this Pilgrimage.

POSTON; PEOPLE OF HOPE…

They are people of hope… That is, the two peoples (the Japanese Americans of the Poston Community Alliance and the Colorado River Indian Tribes) are manifestations of hope. Brought together by the respective injustices that were done to them and the hardships they have endured, these people work together out of a countenance of abiding hope.

[National Archives]

[Densho Digital Archive]

They have a vision. Out in the middle of the desert, near the Arizona/California border, in an area unknown to most, they will build a historical site that will commemorate the imposition of the Camp upon the Indian Tribes, and the imprisonment within the WRA Camp of Americans of Japanese descent.

“The Poston Community Alliance strives to achieve the following:

- Restore existing historic structures located at the Poston Camp I Elementary School Site, now a National Historic Landmark.

- Build an interpretive center and museum.

- Create a multicultural village to tell the stories of the incarcerated Japanese Americans and the Native Americans who shared a desert home during World War II.

- Provide educational materials, including media arts projects, to inform the public of the Japanese American incarceration.”

[Poston Community Alliance Website]

They have a place in which to carry out their vision. Here, they will teach visitors what happened, how it came to be, what the Constitutional violations were, how people suffered and endured and built a new life, and why it must never happen again.

That place is fenced and protected so they can do their work…

Perhaps the most ambitious job will be to somehow preserve the ruins of the Camp 1 Elementary School Auditorium.

Restoring the barracks will show how people lived, in the midst of their captivity.

People will come to the new Visitors Center (to be created in the restoration of this former classroom building) to learn about Poston.

Most important, they have each other… The Poston Community Alliance and the Colorado River Indian Tribes have each other as partners. That partnership is fueled by solidarity of experience, by obvious mutual respect, by dignity, and by tenacity. I am certain that they will succeed in their efforts together.

MINIDOKA: FIRST LOOK…

It is fitting that this guard tower is the first thing you see when driving up to the site of the former Minidoka WRA Camp. It is located right off the road, near the location of the main gate. It is a replica. Now imagine eight or nine of them surrounding the residential and administrative part of the prison camp.

Nearby is a remnant of the Military Police (MP) station at the main gate.

Walking some twenty feet south from the MP station, you come upon the North Side Canal. Built for irrigation of new agricultural lands, the canal formed the southern boundary of Minidoka. As a consequence, rather than the customary rectangle or square, the residential part of the camp was in a kidney bean shape, situated along the arch of the canal.

Minidoka was located out in the middle of sage brush, about 15 miles north of Twin Falls, Idaho.

There is a 1 1/2 mile path that goes through the National Park Service site. On the NPS brochure and website, it looks like there is not much there. However, along the path you encounter many more buildings than you might expect from the time of the camp. For everything you see, there are frequent interpretative placards. This Minidoka NPS site is a nice surprise.

On the path, you come upon a blue gold mine. Well, actually it is the National Park Service’s Visitor Center. Though small, it is fully staffed with an NPS Ranger, Chief of Interpretation Hanako Wakatsuki, other staff, and volunteers. It also has a well stocked book store. Either Hanako or her staff will take you on a tour of the site, filling you with more information than you might have thought possible. Midway along the walking path, the blue building marks the “official” beginning of a visit to Minidoka.

REMNANTS…

Remnant: a small remaining quantity of something. I’m walking along the 1 1/2 mile path that the NPS built on the 400 acre site at Minidoka. All along the path there are 4×4 posts driven into the ground, topped with small metal placards that indicate what had once been on each particular spot.

The sign posts leave us to imagine what it was and how people might have experienced that particular spot during three years of incarceration.

Official vehicles visited this spot frequently, the site of the camp gas station. Cars and trucks moved about the camp, some bringing food supplies for the mess halls, others shuttling camp administrators around the 33,000 acre site, still others bringing in crops from the field.

A portion of an unknown structure sat upon this huge pier.

These pieces of concrete that were once the foundation, floor, and bits of structure of the old warehouse office, are all that remain. We are left to imagine the work that took place in the building – part of the banal organization required to imprison over 9,000 men, women, and children at Minidoka.

Massive piers held the giant water tower that once stood behind the fire station.

These remnants all around Minidoka beckon us. They call upon us to discover what was here, and what happened here in our name. Perhaps, they inspire us to understand why it all happened and to wonder, “Could it happen again?”

RESTORATION AT MINIDOKA…

Walking through the Minidoka site, one comes upon three buildings that reflect key aspects of life in the Minidoka WRA Camp. The historic photo immediately below, hangs in the first of those buildings…

This is a photo of the Minidoka fire house, as it operated in the Camp.

This is the Fire House building as it stands today.

Inside the Fire House, you can see two of the rooms for fire fighters. Because of the additional privacy afforded by the rooms, some fire fighters elected to live in the Fire House all the time.

A large Mess Hall has been recovered and moved into the middle of what was Block 22 at Minidoka. There was one Mess Hall for each block of 12 barracks buildings. This building is in the midst of restoration.

The interior of the Mess Hall. The diagonal braces are to maintain the structural safety of the building, pending further restoration.

One of the early serving tables with period utensils added..

The Park Service moved this old barracks building onto the site, also into the old Block 22. Acquired from a nearby farm, the owner had applied siding as well as a corrugated steel roof to the building.

The interior of the barracks. Awaiting full restoration, the building has a small enclosed room that was added by the former owner, as well as Celotex interior panels. Here again, the diagonal braces were added by the NPS to stabilize the building.

“Each compartment was sparsely furnished. There was really no difference from one to the other for the first couple of years… So everyone tried to be a bit creative, a bit original, get a piece of cloth and you go to sewing school and you make yourself a little curtain, and paintings would be hung on the wall, but nothing really drastic because you could not do anything structurally. So just a few decorative hangings, a different curtain or two, the porch, the wallpaper, the tar paper, the Franklin stove, the bin for the coal, all of that remained pretty well stable with all the compartments, uniformly, very, very similar.”

George Nakata, a young person at Minidoka, [Densho Digital Repository]

Awaiting restoration…

This is the barracks building, with the Mess Hall in the background.

Obviously, there is a tremendous amount of work to be done on both buildings. The impressive thing is the thought, care, and collaboration present in that restoration process. The National Park Service, working with the Friends of Minidoka, has carefully planned, and utilized tight resources to add pieces to the Minidoka puzzle. This careful stewardship is gradually transforming Minidoka into a site which preserves the memory of this important chapter in our history.

HOMESTEADING MINIDOKA…

When WWII ended and the 10 WRA Camps closed, the federal government awarded part of the land for farming to returning WWII Veterans (in 90 to 120 acre plots, along with two barracks buildings). At Minidoka, the government allotted 89 farming units for a total of something near 9,000 acres. They did so via a lottery. The WRA-related action was the last use of the Homestead Act. Japanese Americans from the Camps were not allowed to apply (whether they had farmed land as Camp prisoners or were returning WWII veterans).

In 1950, WWII vet John Herrmann and his family received 90 acres and two barracks buildings, after the original winner of the lottery left the homestead unclaimed. Meanwhile, John Herrmann was recalled to the Army for service in the Korean War. The Homestead Act required that Homesteaders build a home within five years of receiving the property. Time was running out from the initial lottery date in 1947.

This was obviously an impossible situation for Mr. Herrmann. But, the local Soil Conservation District asked Herrmann if they could hold a major farm event, to demonstrate to local farmers the latest farm management techniques. The District organized 1500 volunteers for the event. Over 11,000 people showed up for the all day event on April 17, 1952. The volunteers demonstrated land leveling and plowing of fields, dug a well and irrigation ditches, moved buildings around on the land, and built the Herrmann family home. [Source: National Park Service]

The Hermann family home presently serves as the temporary Visitor Center, but will be converted back to a part of the Minidoka site historic exhibits when the new Visitor Center is completed.

The first of two outbuildings, re-purposed from Minidoka barracks.

The second…

A portion of the original Herrmann family farm yard…

LEAVING MINIDOKA…

My trip to Minidoka came to an end as I walked back through the site of the baseball diamond…

The field was reconstructed by a team of volunteers, the work of the Friends of Minidoka.

How many dreams had been launched on bleachers, watching a game, thinking about life after Minidoka?

I walked past two more of the buildings on the Minidoka site…

An office building of some sort.

A building near the new Visitors Center that is under construction.

As I continued to walk, I could not help thinking about all the young men who had served so valiantly and loyally in the U.S. Army in WWII…

The young Minidoka men listed above, died in combat in the European theater.

I turned to walk out of Minidoka, ready to go back home…

The end of my journey? Not really… Rather, recognizing a life long quest to understand. Why do we allow these things to happen in our country, this place that is a beacon of hope to so many?

“Most white Americans were willing to sacrifice civil liberties in the name of national security as long as they were the civil liberties of someone else.”

Neil Nakadate, in “Looking After Minidoka: An American Memoir”

THANK YOU SO MUCH for coming along on the journey! In the end, it is for all of us a journey of learning, a journey of vigilance, and a journey of hope.

Grace and peace to you,

Art

Art,Thank you for all your time, research, personal resources, intellect and most of all your humanity. Thank you, Roy >

LikeLike

Sincere thanks to you, Roy for your guidance, wisdom, and encouragement!

LikeLike

Hi Art – Sorry too dear about your back, but that’s what you get for woking hard. Let it be a lesson to you, young man! Thanks for all your good work on this project and for reminding us all of a dark time in US history. I think we’re in an even darker time right now, but lets hope we can turn it around a bit in November.

Ashland will welcome you home. Bring your PM 2.5 mask. Now you can get on with your other writing. I’m well into my next book and having a fun time with it.

Peter

Open Your Heart. Quiet Your Mind. Do Good Work.

Peter Gibb Author, Speaker, Teacher Mindful Speaking / Mindful Writing peter@petergibb.org http://www.petergibb.org

>

LikeLike

Hi Peter… Thanks! Good luck with your current book project.

LikeLike

Uncle Art,

Thanks so much for putting this altogether, for taking the time to go and visit these camps or locations were camps used to be. for someone my age it brings to light a new meaning for what went on at these camps and what people truly went through.

Your Nephew

Chris

>

LikeLike

Chris, thanks so much for your comment. I’m glad it was meaningful for you. We can chat about it while we’re fishing! Unc’

LikeLike

Art,

So sorry to learn that your back is barking. I guess that makes us members of the same fraternity.

Your series of travels/reflections/photos has been deeply moving. I expect that I’ll be harking back to your blog in the years ahead and will be pointing others to it, too. What a gift it has been for you to share your faith, curiosity and commitment to justice – and just-remembering – with the rest of us. Thank you!!

With love for you and Thea. It’s going to be hard on Thea and your marriage to have you around home so much…

Your buddy, Phil

On Tue, Aug 7, 2018 at 9:33 PM, JOURNEY of CONSCIENCE wrote:

> revarttrek posted: “Dear friends… It looks like my journey has drawn to > an end. Not that I will ever cease looking into and thinking about this > tragic chapter of American life. Not that I will ever forget the courageous > responses of so many Americans who were treated so ” >

LikeLike

Phil, thanks so much for your comment… Thanks also for you ongoing support. I remember when I was first thinking about this journey, talking with you about the long trip out to Rohwer, Arkansas. I called back, after having expressed doubt about traveling that far for a small site. You said, “I knew that you’d go there out of respect.” You got it so fully. When I’d get a bit tired from the travel, I’d remember our conversation. That’s one great thing about community and friendship… both provide support and a measure of accountability.

Thank you friend for your humor and well wishes… Thea is, indeed, getting used to my being around more and accessible when I’m home. I’m sure that is all to the good. : )

Grace and peace,

Art

LikeLike